By Koreel Lahiri, Program Director for South Asia.

News media in India is going through a challenging period – both politically as well as business-wise. However, the market is large and there is a lot of promise in the digitally native, independent and impactful-content segment. Through this article, I would like to discuss some of our observations, learnings and how this unique market allows us to widen our approach to impact using media and content as key levers.

But first: there are several Indias within India, and without understanding that nuance it would be tough for anyone to create a viable business in this country, much less an impactful one. Also, all these Indias are super-aspirational and do not suffer inferior offerings gladly. This is one of the reasons why several multinational companies have come and gone without making a mark. This backdrop is important because, as I have maintained previously, the business of media is the same as any other business. It operates on the same principles and it serves the same people.

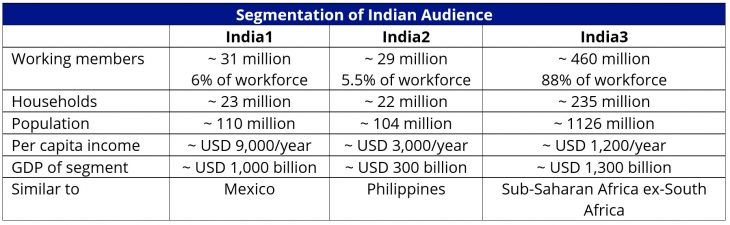

So, what are these Indias? Whichever way you slice and dice it, almost every state, region and language is a large market on its own. But the most fundamental way to segment it would be to divide the country by income levels. Borrowing from an early hypothesis created by a former colleague and a fellow-investor, Sajith Pai, there are three Indias:

Each of these markets has a distinct audience profile, cultural attributes and competitive dynamics, and two major technological developments in the last five years have made it easier for India2 and India3 to get access to services and products: (1) mobile phone (including smartphone) penetration and rapidly declining cost of data; and (2) the emergence of Aadhar (national digital identifier) and UPI (United Payments Interface) as the basic building blocks for access to a digital economy.

But why am I focusing on these structural developments, rather than writing about the media industry?

It is because the needs of the lower strata (India2 and India3), which is the bulk of the nation, is very different from India1. In most cases, the latest generation of this segment is the first that is literate beyond a certain level and is faced with a lack of structured news/information consumption and awareness. This segment is almost 100% non-English speaking, and yet there is very little quality content available in local languages. This, in turn, constrains large parts of society to a narrow worldview defined for them by poor quality information sources and the context set for them by the immediate family/community. Equally important is the form factor – text-based articles are not popular with India2 and even less with India3. Due to this, there has been a shift towards video and more recently towards voice as a mode of preferred content.

Also, important to note is that in a scenario where household incomes are in the range of USD1,200-3,000 per annum, the audience segment is consumed by the grind of daily survival and therefore, very often, it is illogical to expect them to give importance to news beyond its commodified value. Data from Indus OS reveals that out of the average 200 minutes a day that are spent on mobile internet, reading news accounted for just 2%, while more than 40% was for social communication and 19% on utilities and other browsing.

This segment of the population is looking for information that will directly, and without any frills, lead to better lives and economic advancement on a day-to-day basis. For them, information regarding skill upgrading and access to jobs, financial literacy, healthcare, entrepreneurship, access to government services, etc. form the core of their needs; news and information they can use. This is followed by their rights as citizens and ways for them to access and protect those rights.

There is a massive opportunity to create platforms for solving specific content needs of this vernacular and hitherto unaddressed user base. Social-plus content platforms are uniquely positioned to achieve scale and benefits via shared interests and motives of a particular community. For example, women are severely under-represented in the Indian internet. Purpose-driven platforms, like our portfolio company Sheroes, give not only a safe space for expression but also a highly engaged community that shares values and purpose. This enables them to create opportunities for women to access healthcare information, legal assistance, enable financial inclusion, improve skills, etc.

Similarly, underprivileged youth find a common cause to engage with skills development platforms like Josh Talks and Josh Skills in a way that traditional ed-tech has largely ignored. The shared values emanate from the deep desire to master soft skills, like speaking English, for greater acceptance in the professional world. Even a purely rural-focused voice-tech community platform like Gram Vaani benefits from the shared value of grievance redressal and rarely heard stories from rural India.

These platforms are going beyond providing merely news – they are providing an even more fundamental building block that is empowering citizens to make more informed life choices; of course, the ability and desire to participate in the democratic process being one of them.

If by now you think that regular news is dead; well, it isn’t. Even that has evolved, but at the top end of the pyramid. While the large horizontal news websites and broadsheet papers serve undifferentiated and often poorly fact-checked news to the masses, there is an emergence of platforms that are singularly focused and go very deep in their reportage. These are either completely behind paywalls catering to a premium audience (like The Morning Context, Scroll, Splainer, The Ken, ET Prime, etc.) or are boutique story-telling units producing long form, factual infotainment for OTT platforms (Arre, Confluence, etc.).

The bottom line is that all three Indias are evolving fast and have unique information needs, and in each case legacy has rapidly yielded room to digital by not recognising the shift in audience preferences. Moreover, the twin structural levers of Adhaar and UPI are enabling both organisations and consumers to vet sources of information and enable seamless payments (without requiring cards).

One of the most popular narratives that the bottom of the pyramid doesn’t pay is being proven wrong. They don’t pay for frivolous non-essentials, but they pay for everything that they deem essential from the view of improving their standard of living, health, education, etc. What they need is access to quality information in a language they understand, ability to interact with people they relate to, and a format they are comfortable with.

This article is part of our series, ‘25 things we’ve learned’, marking MDIF’s 25th anniversary.