By Tosca Santoso

Thanks to social media platforms, media are succeeding in increasing their audiences. Revenue sources are another matter.

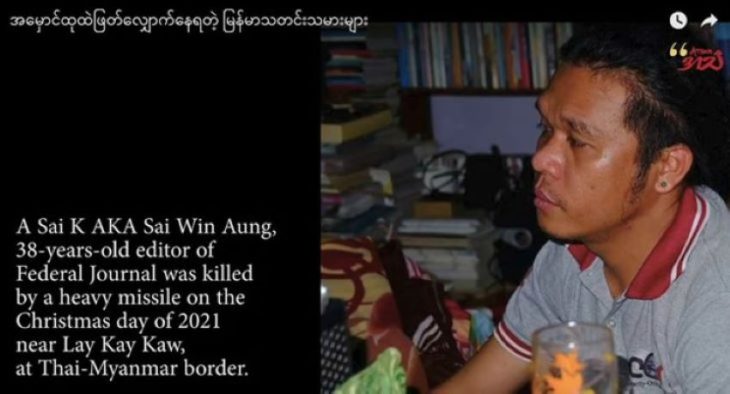

Around 10 people surrounded the open grave. They were paying their last respects to two young men, journalist A Sai K and activist Oak Gye, who had been killed by a mortar blast during an artillery attack by the Myanmar military near Mae Wah Kee village in Myawaddy township, Karen state. The area is usually controlled by the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), a Karen ethnic armed organisation. Since the coup, a few media had moved there in the hope that it would be a safer location from which to work. But the attack last Christmas proved that nowhere is safe for journalists in Myanmar.

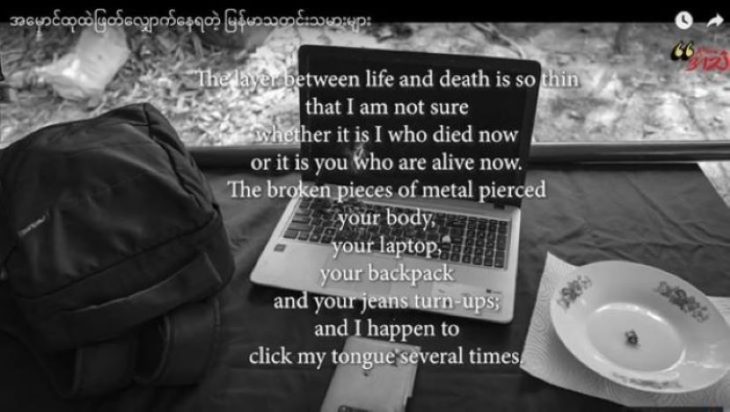

You can watch this scene in Walking Through the Darkness, a documentary released on 3 May 2022, World Press Freedom Day. Soe Ya, a journalist and poet, and the founder of a local media organisation, Delta News Agency, describes the fateful day sorrowfully. “I try to imagine that he’s sleeping in the forest,” he says, to feel a little better. Even though he knows that his friend will never wake up.

After the burial, So Ya repaired A Sai K’s backpack, which had been damaged in the explosion. He found 1,000 Kyat ($0.50) in cash and a bank book showing a balance of just 7,596 Kyat ($4). His friend had less than $5 to his name when he died. Soe Ya joked sarcastically that he had anticipated a big bequest. But it turns out that all his friend had was what was in his rucksack when he met his end. It makes you wonder what makes Myanmar’s young people take such huge risks, of imprisonment or even death, for the sake of independent media, when they get so little financial recompense in return.

Since the February 2021 coup, Myanmar’s independent media have been forced to go back to operating as they did during the previous military dictatorship. Working underground or from across the border in Thailand or India. But, unlike in the 1980s, nowadays there is the internet. The global digital network makes it easier for them to reach their audiences, an advantage that didn’t exist for independent media operators back then. Media like Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), Mizzima, or the Karen Information Centre (KIC), which already had experience of facing up to a military regime, have quickly reverted their modus operandi back to the old ways, with the bonus of the internet to speed up and extend their reach.

The data MDIF has compiled about the reach of its ethnic and other local media partners across the country confirms that their audience numbers have grown dramatically. Between January and December 2021, 10 of MDIF’s partners saw, on average, digital audience growth of 93%. Their Facebook and YouTube followers more than doubled, from five to more than 11 million. Such growth is staggering. While a more detailed look shows their website visitors declined, on average by 46%, by contrast their YouTube and Facebook follower numbers grew dramatically, by 489% and 118% respectively. On one hand, this shows the vulnerability of Myanmar’s independent media, which are increasingly dependent on social media, but on the other it is very positive because their audiences have grown so significantly.

This trend isn’t only limited to ethnic and local media, as national media such as Mizzima and DVB have also seen extraordinary increases in their audience numbers. Mizzima’s founder, Soe Myint, regularly proudly uploads the numbers on his Facebook page. As of 14 July 2022, Mizzima has over 25.5 million followers on its three Facebook pages for Mizzima English, Burmese and TV, as well as more than 1.4 million YouTube subscribers and 27,500 Telegram users of its channel. Such reach was never envisaged when Mizzima started operating as a small, cash-strapped media in exile in India back in 1998.

The internet has made it much easier for independent media to reach their audiences and to provide them with accurate information. Even though the military regime bombards the public with propaganda through state-owned media and continually tries to suppress independent voices, nowadays the public has options. It will be interesting to see the impact of these very different information flows in influencing Myanmar citizens’ opinions in the longer term.

Prior to the February 2021 military coup, five out of 10 of the media partners that MDIF was working most intensively with had print publications. Those like Dawei Watch, a local media based in the southernmost region of the country, published weekly, while Karen ethnic media, KIC, had a monthly journal. But the coup made print media distribution difficult. Even regular subscribers did not want to take the risk of receiving them. This challenge forced these media to halt their print operations and to switch exclusively to digital.

As noted above, their reach increased significantly, but operating fully in the digital world brings its own challenges. Technical skills and digital literacy are an absolute must for newsrooms. Their reliance on social media platforms, especially Facebook and YouTube, means that editorial staff need to understand and abide by these platforms’ community standards to avoid their accounts being frozen and social media monetisation possibilities being blocked. Several MDIF media partners have been sanctioned for violating community standards that they were not aware of or didn’t understand.

MDIF tightened its program focus in response to these changes and increased digital support to its media partners. Providing technical assistance direct to each media, MDIF offered digital training and workshops on community standards. MDIF also translated Facebook and YouTube’s community standards to Burmese to facilitate comprehension. This program helped the ethnic and other local media to manage their now totally digital platforms; and to try to build revenue streams from them.

During 2021, MDIF’s 10 main media partners earned between $100-1,000/month in digital revenue, mainly from YouTube and Facebook. While still small compared to their operating costs, it has been very meaningful for media who have lost almost all their other revenue streams since the coup. Advertising, previously an important source of revenue for independent media, has dried up since the coup. Media that originally earned income from selling their publications, have seen that source vanish too. For independent media in Myanmar, social media revenue looks set to be increasingly important in the future.

Unfortunately, social media platforms ignore traffic from Myanmar as a monetisation opportunity. This means that, despite many independent media’s content being viewed or read by sizeable audiences in the country, they are unable to generate income from their output. Or, if they can do so, the amount is far smaller than their traffic numbers should dictate.

With so few revenue sources available, MDIF’s initiative to commission their media partners to produce and disseminate Public Service Announcements (PSAs) has proven extremely useful. So much so that some of them rely on it for 100% of their revenue. The revenue they get from the MDIF PSA Initiative not only covers their operating costs, it also provides important information to their audiences. Over the past year, most of the PSAs have focused on information about COVID-19. But now the themes are expanding to cover topics ranging from migrant worker rights to environmental issues, landmines and media literacy. If international organisations active in Myanmar were to participate in this program, it could be an effective and practical way to boost ongoing support to independent media there, while also disseminating valuable public service information.

This is a long journey. Who knows for how long the military regime will suppress media freedom in Myanmar? But the determination of journalists to run independent media will not end. A Sai K lies in a rubber plantation in Karen state. His colleagues will continue their work to serve the people.

Photo credits: Walking Through the Darkness documentary, released 3 May, 2022

This article is published on Martyr’s Day, a Burmese national holiday to commemorate the assassination in 1947 of General Aung San and seven other leaders of the pre-independence interim government, and one bodyguard. Today, we would also like to commemorate the more than 2,000 pro-democracy activists and other civilians who have been killed since the February 2021 coup, including journalist A Sai K and activist Oak Gye.

Tosca Santoso founded and was CEO for 15 years of Indonesia’s first independent national radio news agency, KBR. He also co-founded the country’s leading independent journalists’ association, the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI), in 1994. For the past seven years Tosca has been a coach for Media Development Investment Fund’s business capacity building program, Myanmar Media Program (MMP).